Mourningdress a Christmas Carol Why Does Belle Wear

The End of Scrooge's Early Love Story

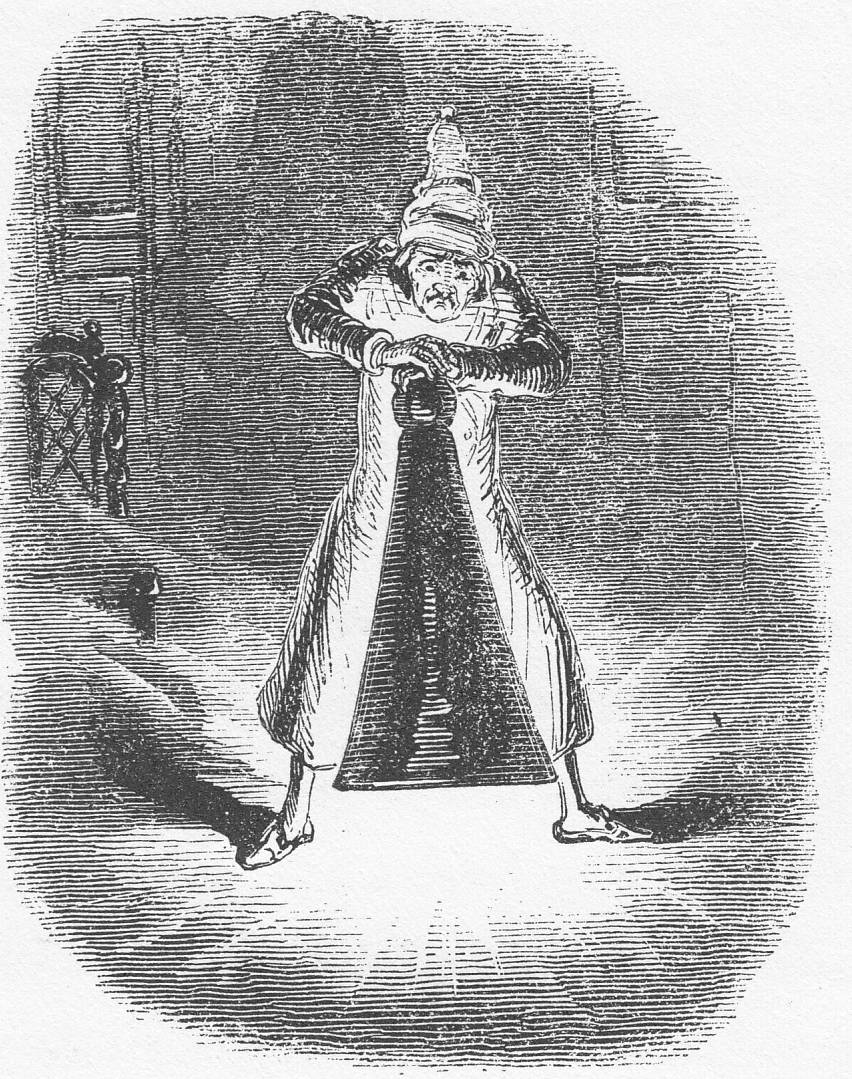

Charles Green

c. 1912

12 x 10.8 cm, vignetted

Dickens's A Christmas Carol, The Pears' Centenary Edition of The Christmas Books, I, 63.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

![]()

Context of the Illustration: The Golden Calf versus the Engagement Ring

For again Scrooge saw himself. He was older now; a man in the prime of life. His face had not the harsh and rigid lines of later years; but it had begun to wear the signs of care and avarice. There was an eager, greedy, restless motion in the eye, which showed the passion that had taken root, and where the shadow of the growing tree would fall.

He was not alone, but sat by the side of a fair young girl in a mourning-dress: in whose eyes there were tears, which sparkled in the light that shone out of the Ghost of Christmas Past.

"It matters little," she said, softly. "To you, very little. Another idol has displaced me; and if it can cheer and comfort you in time to come, as I would have tried to do, I have no just cause to grieve."

"What Idol has displaced you?" he rejoined.

"A golden one."

"This is the even-handed dealing of the world!" he said. "There is nothing on which it is so hard as poverty; and there is nothing it professes to condemn with such severity as the pursuit of wealth!"

"You fear the world too much," she answered, gently. "All your other hopes have merged into the hope of being beyond the chance of its sordid reproach. I have seen your nobler aspirations fall off one by one, until the master-passion, Gain, engrosses you. Have I not?"

"What then?" he retorted. "Even if I have grown so much wiser, what then? I am not changed towards you."

She shook her head.

"Am I?"

"Our contract is an old one. It was made when we were both poor and content to be so, until, in good season, we could improve our worldly fortune by our patient industry. You are changed. When it was made, you were another man."

"I was a boy," he said impatiently.

"Your own feeling tells you that you were not what you are," she returned. "I am. That which promised happiness when we were one in heart, is fraught with misery now that we are two. How often and how keenly I have thought of this, I will not say. It is enough that I havethought of it, and can release you."

"Have I ever sought release?"

"In words? No. Never."

"In what, then?"

"In a changed nature; in an altered spirit; in another atmosphere of life; another Hope as its great end. In everything that made my love of any worth or value in your sight. If this had never been between us," said the girl, looking mildly, but with steadiness, upon him; "tell me, would you seek me out and try to win me now? Ah, no!"

He seemed to yield to the justice of this supposition, in spite of himself. But he said with a struggle," You think not?"

"I would gladly think otherwise if I could," she answered, "Heaven knows. When I have learned a Truth like this, I know how strong and irresistible it must be. But if you were free to-day, to-morrow, yesterday, can even I believe that you would choose a dowerless girl — you who, in your very confidence with her, weigh everything by Gain: or, choosing her, if for a moment you were false enough to your one guiding principle to do so, do I not know that your repentance and regret would surely follow? I do; and I release you. With a full heart, for the love of him you once were."

He was about to speak; but with her head turned from him, she resumed.

"You may — the memory of what is past half makes me hope you will — have pain in this. A very, very brief time, and you will dismiss the recollection of it, gladly, as an unprofitable dream, from which it happened well that you awoke. May you be happy in the life you have chosen."

She left him, and they parted. ["Stave Two: The First of The Three Spirits," 61-64: the original caption has been emphasized.]

Commentary

Illustrator Charles Green underscores Belle's cancelling the engagement as a key psychological event in Ebenezer Scrooge's moral and emotional development as it reiterates his being rejected by his father and being abandoned by his classmates at each Christmas break when he was a boy at school. Seeking security and control over the events of his life, as a young man Scrooge committed himself to the pursuit of wealth as symbolized by the Golden Calf which the Israelites elected to worship in Exodus. His cupidity as a form of self-love has come between the now-adult Scrooge and his fiancée, Belle. She has correctly interpreted the signs of Scrooge's succumbing to the allure of owning more and more personal property, for things rather than people now matter to him, as Dickens makes clear. However, Dickens only offers the tantalizing clue of Belle's being in deep mourning as the reason why she has chosen this moment to break off the long-standing engagement.

Thus, as with Scrooge's father's rejection of his son, Dickens leaves the back-story of the miser's blighted hopes for home and family somewhat open-ended, even though Dickens clearly indicates that, for his protagonist, greed has displaced love and monetary calculation kindness. The author does not even stipulate when and where this conversation occurs (other than "in the open air"), although the film adaptations suggest that it occurred after one of those office parties for which the kindly Fezziwigs were famous, in the precincts of the warehouse. Green sets the scene in a park, foregrounding the distraught Belle and thrusting a dapperly dressed Scrooge into the background, standing by the bench where, presumably, most of the rejection scene has transpired. Green's way of flagging this emotionally significant moment for readers of the 1912 text is to give the illustration its own page, one of just nine scenes to receive such treatment. Were Scrooge not still possessed of "nobler aspirations," Belle would not grieve — and Scrooge would not be capable of moral and social regeneration in the present.

As in the text and the 1868 Eytinge illustration of the same moment, A Retrospect, Belle is depicted as "a fair young girl in a mourning-dress," but otherwise the illustrators have been free to improvise, particularly with respect to the figures of the couple: businessman Scrooge, for example, is younger and much better dressed in the Green interpretation of the scene. Pointing not merely toward the scene but a future devoid of companionship, in the Sol Eytinge, Junior, wood-engraving (1868) the Spirit of Christmas Past is upstage (left), in the very centre of the composition, which is otherwise dominated by Scrooge, his back towards us, wringing his hands. Although Dickens indicates that Scroogeand his spirit-guide are "in the open air," Eytinge has set the ensuing dialogue between Scrooge and Belle indoors. Green, in contrast, uses a park-like setting, just the sort of private space for Belle's confronting her fiancé about his growing love of gain and his much reduced interest in her, "a dowerless girl" (62) by her own account. Creating a great gulf between Scrooge, silhouetted against a stand of birches in the background, and inward-looking Belle in the foreground, Green adopts an entirely different compositional strategy from Eytinge's, placing the overwrought Belle close to the reader, who, unlike Scrooge, can assess by her expression the pain that this interview has cost her. Significantly, Green does not show either Scrooge the dreamer or The Spirit of Christmas Past, so that the moment has all the reality of a motion-picture still. The eye is drawn forward diagonally from Scrooge as "man in the prime of life" (60) and the vacant bench down the path towards Belle, listlessly gripping the handle of her umbrella. To heighten the contrast, Green has Scrooge in light hat and trousers. The symbol of their life together that might have been is the empty bench, designed to seat two. Scrooge is seen at too great a distance for the reader to gauge his emotions, so that the reader must return to the text to assess how re-living this incident has afterwards affected Scrooge, who has not, contrary to Belle's confident assertion, "dismiss[ed] the recollection of it" (64). He tries to do so now, of course, as John Leech's tailpiece for Stave Two, Scrooge Extinguishes the First of The Three Spirits (see below, from the 1843 edition, 73), makes clear. Indeed, Green has eliminated the spirit-guide entirely from his illustrations for Stave Two, emphasizing that these are images of the protagonist's memories, not pageant scenes displayed by a supernatural agent.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1843 and 1868 Editions

Left: Eytinge's scene of Scrooge's being rejected, A Retrospect. Right: Leech's interpretation of Scrooge's attempting to suppress painful memories, Scrooge Extinguishes the First of The Three Spirits.

Illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843-1915)

- John Leech's original 1843 series of eight engravings for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867-68 illustrations for two Ticknor & Fields editions for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Charles E. Brock's 1905 illustrations for A Christmas Carol and The Chimes

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A selection of Arthur Rackham's 1915 illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. VIII.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by Charles Edmund Brock. London: J. M. Dent, and New York: Dutton, 1905, rpt. 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 6 August 2015

Last modified 5 March 2020

Source: https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/green/54.html

0 Response to "Mourningdress a Christmas Carol Why Does Belle Wear"

Post a Comment